I’m big on noticing nature. There’s always something to watch and wonder about—from a line of busy ants to the flicker drilling on the maple tree to the clouds drifting by. Paying attention to the world outside has always helped me feel connected and I’ve tried to help others capture that feeling, whether it is showing young neighbors what’s growing in my garden, birding with my dad, or taking my kids on wildflower walks.

Books are part of making that connection to nature in our family, helping us find nature right outside our window and in faraway places. And Nicola Davies is one of our go-to authors for books about the natural world.

Nicola is the author of more than 90 books for children: fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. Some of our favorite titles of hers include Outside Your Window: A First Book of Nature, Poop: A Natural History of the Unmentionable, Song of the Wild: A First Book of Animals, The Lion Who Stole My Arm, and Gaia Warriors. She trained as a zoologist and worked as a field biologist, studying humpback and sperm whales, and bats, before joining the BBC Natural History Unit as a researcher and then presenter.

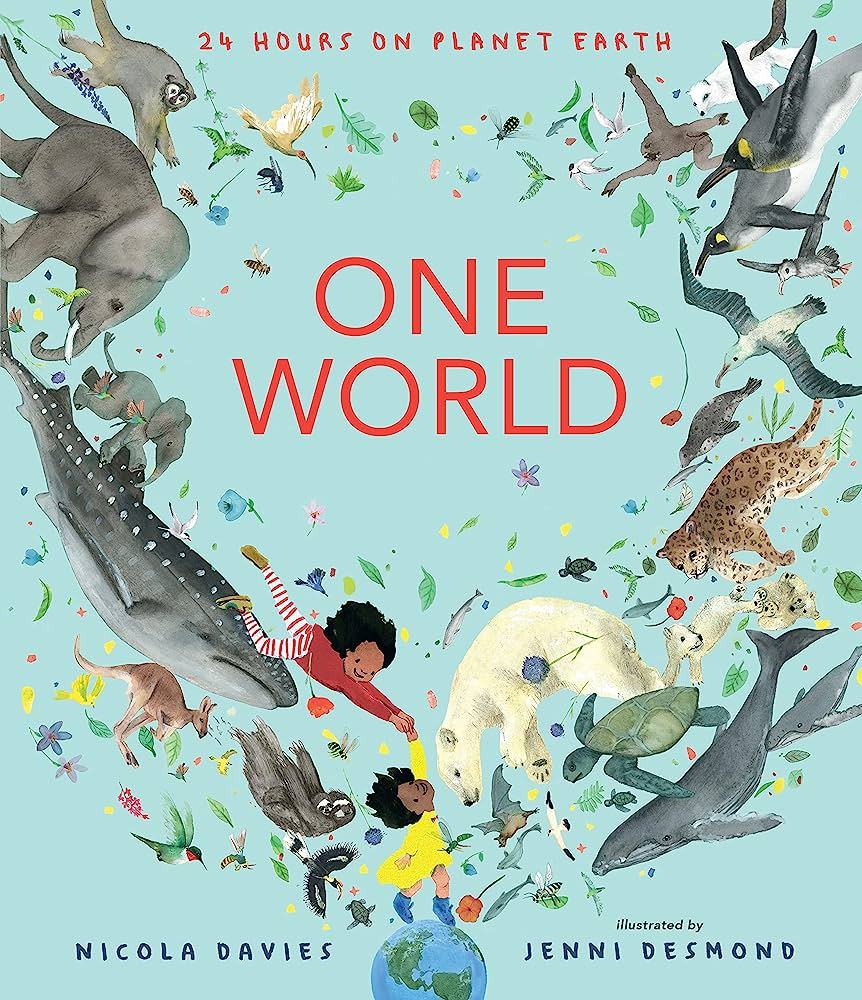

Over the past forty years and thousands of conversations with children, Nicola has emphasized how important it is that we understand all that nature does for us. Her new book One World: 24 Hours on Planet Earth, from Candlewick Press, reminds us of just how essential that understanding is. I’ve also found it to be an excellent title for launching many of the climate and climate change related activities in Weather Wonders.

We are thrilled to have Nicola here sharing things to think about, talk about, and do to better appreciate our incredible planet.

One World: Nature as Our Ally by Nicola Davies

July 5, 2023

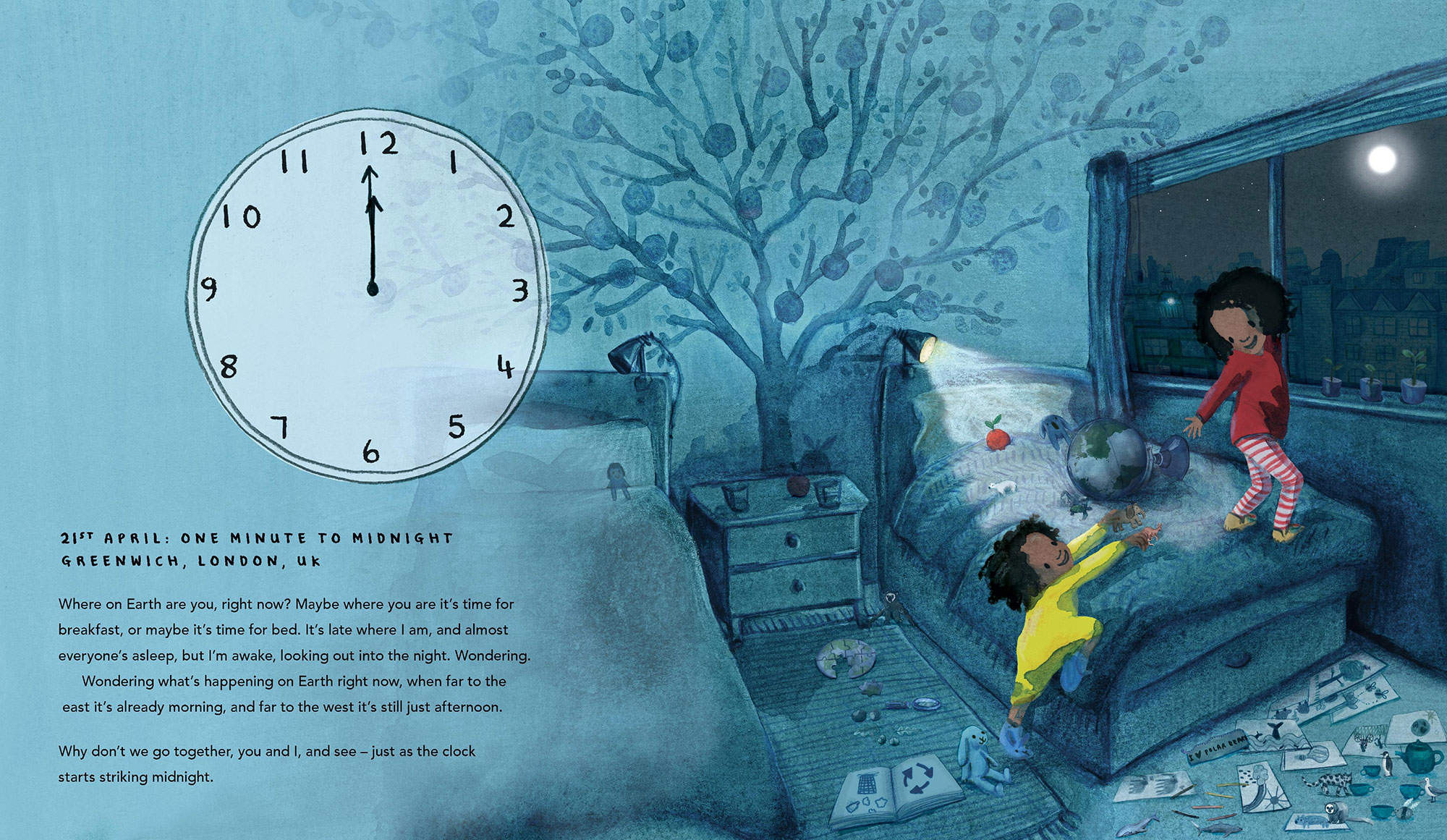

One World: 24 Hours on Planet Earth begins at midnight, a time of magic and transformation in all stories. But although the journey that the two children make is one that happens in their imaginations, spanning the whole globe in the time it takes the clock to strike twelve, the places they visit are real. The children visit wild locations on land and in the ocean, at dawn, midday, dusk, and night, experiencing different time zones and a variety of different habitats.

On one level, this is a story to encourage a sense of wonder about the natural world and to bring about an awareness of the extraordinary and marvelous life in which our planet is still clothed. I loved to look at maps as a child, to trace coastlines, mountains, and forests and imagine what animals and people lived under the track of my curious finger.

It made me want to explore the world, but it also thrilled me to think of jungles and deserts, mountaintops and ocean trenches existing at the same time as me, right now, on Earth. I loved to think of the world turning, with light and darkness following each other across the curved face of the planet, and all of us, humans and animals and plants, aboard our natural “spaceship.” The delight that I felt back then has never left me, and I hope One World will help readers share it. Although I have been lucky enough to explore the Earth a bit, there are many places I will never get to, many creatures I will never see, yet I still delight in them. Just knowing that I share my home world with giant anteaters is enough, even if I never get to see one in the wild!

But One World has another layer of information and meaning. In each place they visit, the young travelers learn about threats that these wild places face from human activity—deforestation, hunting, climate change—and what humans could do and are doing to help. I know that some adults think children should not be presented with any of life’s harsh realities, but in the modern world of TV and smartphones we can’t wrap our kids in bubble wrap. I feel it’s my job as a writer for children to tell them the truth about their world in a way they can understand. And the truth about the natural world is that, although we humans have caused terrible destruction, there is hope. Given the chance, nature can recover and thrive, and humans can choose to give nature that chance.

In the face of climate chaos and biodiversity crisis, I know that many children—and adults—feel afraid and powerless. The messages delivered by mainstream media either ignore the problems altogether or are very negative, encouraging a feeling of hopelessness. So my aim in writing One World was to counter both ignorance and negativity: to outline problems clearly but show that there are solutions, to demonstrate that humans can change their behavior, and to invite children to be part of that change.

Climate change is a huge problem. It will come to dominate the lives of the next several generations of humans. But in our efforts to combat climate chaos, nature is our greatest ally. Restoring the diversity and balance of complex ecosystems on land and in the ocean will soak up more carbon than any human geoengineering project ever could. Reading One World and talking about the issues it raises with your child is a way to help with that restoration because it begins with knowledge, and with the ability to imagine the real wild places that nourish and create our One World.

Things to talk about, things to do

Map Your World

Look at maps. Start with one at the scale of your locality and make a copy your children can draw on. Encourage them to mark places they know and things they’ve seen, especially plants and animals—old trees are a good thing to mark. Talk about what your map might have shown twenty, fifty, one hundred, and two hundred years ago. What could be added or taken away from your map for there to be more animals and plants?

Do the same with maps that show bigger and bigger areas: the whole county, the whole state, the whole continent, the whole world. Research what animals and plants are found at different locations on your maps.

Map Your Family/Friends/Community in Space and Time

Where on the map are the people you care about? Where were they five years ago? Talk to people in your community, especially the old ones, and map where they were when they were children. Where on a map might your own great-grandchildren be?

Be a Good Ancestor

Some Indigenous people have a tradition of looking back seven generations—210 years—and forward seven generations so they can learn from the past and do the best for the people who come after them. Are there things in your environment that were put there by a person 210 years ago—big buildings or old trees, for example? What can you do to make life better for people 210 years from now? How might doing something good for your descendants make you feel?

Resources

- Nicola Davies website

- Growing the Glasgow Children's Woodland Documentary of The Lost Woods

- Start with a Book: Weather Wonders

- Start with a Book: Nature: Our Green World